Illustration of Alan Kurdi by Yante Ismail © UNHCR/Yante Ismail

Jean-Nicolas Beuze, UNHCR Representative in Canada, writes on the second anniversary of the death of Alan Kurdi with a question; as the world moves on and the headlines fade, have we done enough to protect refugees who are most vulnerable?

On 2 September 2015, we all awoke to the image of a lifeless three-year old Syrian boy’s body washed up on the shores of a Turkish beach. We later learned his name, Alan Kurdi, and his story. He had died trying to seek safety in Europe with his family. Instantly, this tragic image and the subsequent images of his smiling face became a rallying cry for the refugee cause.

Not long after, the Canadian government increased its refugee resettlement quota resulting in Canada welcoming 46,702 refugees: a record! While this action was in many ways called for and supported by the Canadian public, it seems as though support may have diminished over time, in the same way as this tragic image has slowly faded from public memory. Therein lies the reality of an event that forces reactions from the world: the impact is often temporary. Countless tragedies have made headlines to be soon forgotten, while victims whose stories remain untold are still expectantly waiting for the international community, you and me, to show solidarity and demonstrate to them our belief in a common humanity.

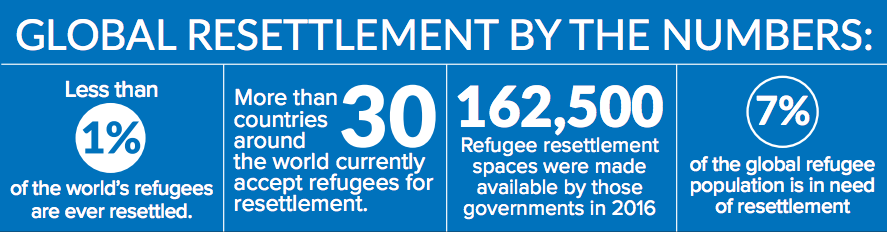

In many ways, we seem far worse off in 2017 than we were in 2015, as support for assisting refugees is losing ground in an increasingly isolationist world. There are currently 65 million people forced to leave their home to seek safety, often forced to resort to the most dangerous and irregular routes. And many end up like Alan Kurdi; since 2015, an estimated 8,500 refugees have lost their lives in search of protection by crossing the Mediterranean Sea. Globally, out of the 22.5 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18, my agency, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has identified 1.2 million refugees that are in need of urgent resettlement for survival. Yet, it will probably only be able to resettle 8% of those refugees – a drop of 2% from last year.

This means that in 2017, 24,000 individuals will not be given the possibility to rebuild their life in a third country like Canada. Resettlement for them – a rape survivor, a widow with several children with no source of income, a lesbian at risk of an honour killing, a person in a wheelchair currently living under a plastic sheet or a student who’s been tortured for having peacefully demonstrated – means survival, plain and simple. Those we identify as needing resettlement are those who cannot survive in the country where they first found refuge, mainly in Africa and the Middle East.

In 2017, Canada will contribute to 0.75% of these resettlement needs. That is a total of 9,000 refugees from the 1.2 million we identified: all names and stories recorded by us and who now wait for a light at the end of the tunnel. Since I arrived to Canada nine months ago, I have heard time and again from Canadians of all walks of life that we have proudly shown what we are capable of doing, but that “we can do better”. As a nation protected by oceans and far removed from crises, we may not always realize the scale of what is needed and how it affects us personally. The world’s developing countries are currently shouldering the largest burden, 84% of the world’s refugees are hosted in countries such as Lebanon, Jordan, Uganda and Kenya. All countries I have worked in, and like in Canada, countries where the population has shown their strong solidarity and extreme generosity towards refugees.

On the anniversary of Alan Kurdi’s tragic and unnecessary death, one needs to remember the individual faces that tend to get lost among the millions of refugees that need a tangible demonstration of our humanity.

Faces such as Maria’s. While still just a sixth-grader, gang members started to harass Maria, a fourteen-year old girl from El Salvador. Known as pandilleros, the criminal gangs routinely force girls and boys into their ranks, the girls as their sex objects and the boys as foot soldiers. Maria’s parents pulled her out of school. They knew what the gangs were capable of doing. In 2008, during the emerging stages of the gang violence, Maria’s sister went missing at the hands of a local gang and was tragically never seen again. Eventually, Maria had no choice but to flee for safety. Not to get a better life in North America – as is too often the narrative portrayed by some – but to escape what Alan and his family were also escaping: unimaginable violence and persecution inflicted by other human beings.

Jihan embraces her five-year-old son, Ahmed, as Mohammad, who is seven, strolls on the boardwalk by the harbour in Lavrio, Greece. UNHCR/A D’Amato

As I am writing this note from Napoli, Italy, I also think of the face of 34-year-old Jihan who was willing to risk everything in order to escape war-torn Syria and find safety for her family. Jihan is blind. She fled Damascus with her husband, Ashraf, 35, who is also losing his sight. Together with their two sons, Ahmed, 5, and Mohammad, 7, they made their way to Turkey, boarding a boat with 40 others and setting out on the Mediterranean Sea. I saw all these faces when I was visiting desperate refugees in Lebanon. Mothers telling me they would risk everything to give an education to their kids, or sons getting ready to cross oceans to seek medical treatment for their dying fathers.

Amiir with his wife and child. UNHCR/I Ibba

I think of Amiir, from Somalia, who arrived to Italy by sea in May 2014 with his wife and newborn daughter, after a long journey that took him through Ethiopia, Sudan and Libya. Imagine what they must have gone through. Imagine what they must have felt when they were rescued by an Italian vessel. By the time they reached Italian soil, Amiir’s daughter who was just two months old and had already spent ten days of her young life in a tiny, overcrowded boat.

After hearing such stories or meeting such courageous people, I often ask Canadians if we can do more. The response is more complex than the simple “yes” that is suggested here. I know. Yet behind every number there is a human being and refugees are people who over time have become part of the Canadian mosaic, helping to make Canada the beautiful country that it is today. I still cannot shake that number from my mind: just 0.75% of the most vulnerable refugees will be welcomed to Canada in 2017. So I feel one should ask the question again: is this enough?

Jean-Nicolas Beuze is the Representative of UNHCR in Canada. Beuze has worked in international humanitarian organizations, including various United Nations Agencies for 19 years. Most recently, Beuze was the UNHCR Deputy Representative for Protection in Lebanon where he led the Inter-Agency Coordination for the refugees and resilience response plan between the Government of Lebanon, UN agencies and NGO partners, and donor countries.

DONATE TO HELP REFUGEES NOW