Young Rohingya leapt into the sea to retrieve supplies dropped by a helicopter on 14 May. © UNHCR / Christophe Archambault

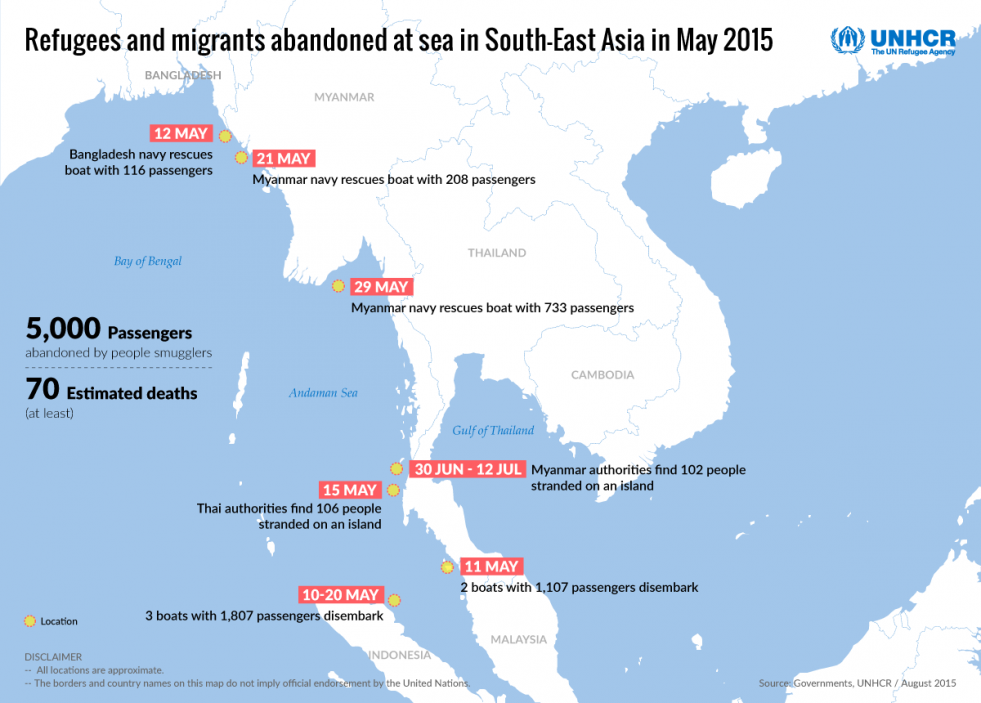

In May of this year, at least 5,000 refugees and migrants from Myanmar and Bangladesh found themselves stranded at sea when the people smugglers and ship crews who had promised to take them to Malaysia abandoned them en masse in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

Governments in the region initially refused to conduct search-and-rescue missions, or to allow any of the passengers to disembark. Soon viewers around the world were riveted by images of emaciated men, women and children leaning over the sides of the boats, begging for food on the open sea.

Since January 2014, over 94,000 people are thought to have departed by boat from the Bay of Bengal along this route. About half are believed to be Rohingya from Rakhine State in western Myanmar. Based on over 1,000 interviews with Rohingya who have made the journey, UNHCR estimates that for every 1,000 passengers aboard smugglers’ boats, 11 or 12 never again set foot on dry land. Instead, they are either beaten to death by the crew or succumb to starvation, dehydration, or disease. Untold others have perished in jungle camps in Thailand and Malaysia where smugglers hold them for ransom, and where the remains of over 200 people have been discovered in recent months.

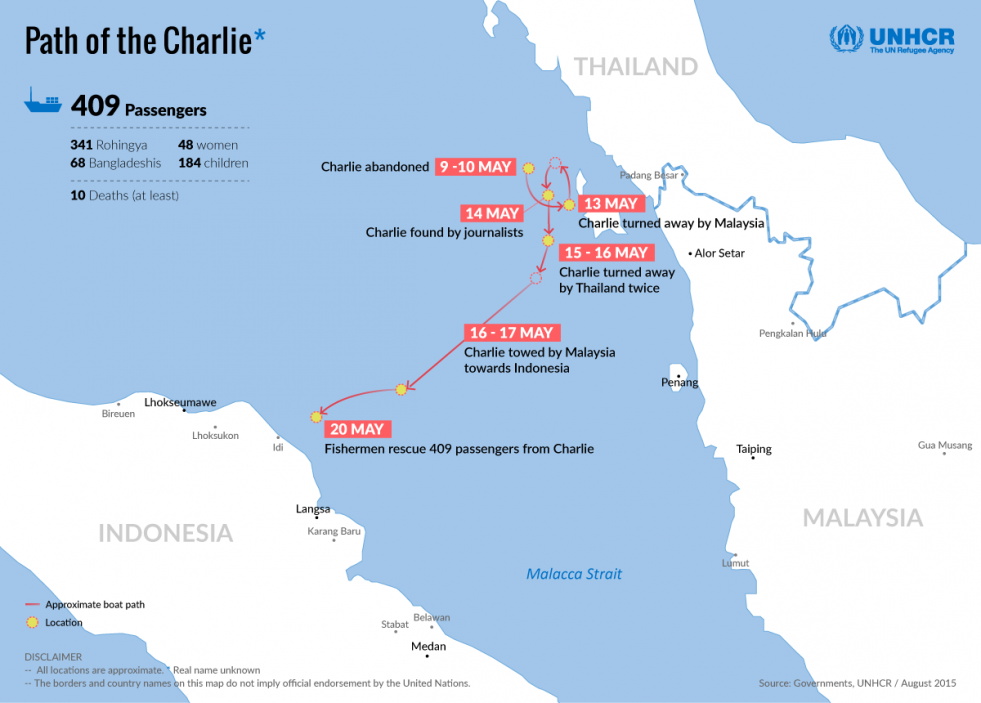

Survivors of the deadly impasse in May shared haunting memories of being smuggled and stranded at sea. The names of the three boats are unknown, but to distinguish one from another we refer to them here as the Alpha, the Bravo and the Charlie.

At least 70 passengers lost their lives during the widely televised crisis earlier this year in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. © UNHCR / Younghee Lee

THE ALPHA

The sun was beginning to dip below the horizon on 14 May 2015 when young Setara Begum fell swiftly through the air, past the boat’s dark grey hull. Her malnourished body, slight even for an 11-year-old Rohingya girl, slipped invisibly into the water, with a splash that was drowned out by the screaming on board. Dozens of other bodies were falling around her, fellow victims of a desperate melee in the Malacca Strait, about 100 kilometres east of Langsa, Indonesia.

“It was chaos, panic,” recalls her mother, Kulsuma, describing the incident two months later. “I didn’t notice her.”

Kulsuma had lost sight of Setara while struggling to save her two young sons, the eldest of whom she had wrenched from the clutches of a mob of Bangladeshi men. “They were trying to pull him below deck,” says Kulsuma. “To slaughter him.”

“It was chaos, panic.”

“If we die, you all will die, too,” the Bangladeshis shouted, enraged that the Rohingya men seemed to be reserving the last of the water for themselves. A group of men reached for whatever tools were left on the ship—iron rods, crowbars, axes—and swung them through the cramped hold with abandon.

Soon, the combat spilled onto the main deck, where passengers pried off wooden planks to be used as flotation devices or bludgeons. One Rohingya teenager, who had fled his home in Maungdaw, Myanmar, after being beaten by local authorities, was struck in the face with a wooden plank, tearing open his eyebrow and cheek. With nowhere to run, he jumped from the deck and hit his side against the ship as he dropped into the seawater, reigniting the sting in his wounds.

Ali Ahmad* of Muangdaw, Myanmar, was struck across the face with a wooden plank during a vicious fight for drinking water aboard the smugglers’ boat that took him to Indonesia. © UNHCR / Tarmizy Harva

It wasn’t long before the boat, its hull punctured, began to sink. The women and young children, all Rohingya and largely spared from the fighting, now considered jumping as well. Three cousins stepped to the edge of the ship and cried as they embraced.

“Save your own life,” shouted the oldest. “God willing, we might see each other again.”

They jumped, along with over a dozen women nearby. One, a Rohingya woman from Maungdaw who had hoped to join her husband in Malaysia, jumped with her two-year-old son. In the water, unable to swim, she lost him.

“Save your own life,” shouted the oldest. “God willing, we might see each other again.”

Abdul Jolil, a tall and broad 37-year-old man from Kyauktaw, Myanmar, was running to where the women had gathered when, from over the edge of the ship, he saw a woman drowning. She had jumped into the water after her husband was knocked overboard. Their four children, none older than 10, were in the water, too, frantically trying to hold on to their father. He had no strength left to stay afloat, let alone carry his children.

At his feet, Abdul Jolil noticed a couple loose planks nailed together, meant to cover the engine below. He picked the planks up and threw them into the sea, towards the family, then jumped into the water himself. But the woman never got hold of the planks. Minutes later, her body floated to the surface, and her younger son clung to it, weeping. As her older son, Yasin*, treaded water nearby, another limp body surfaced, of Yasin’s father, and then another, only much smaller: Yasin’s five-year-old sister.

On the ship, with darkness falling, the hull kept taking on more and more water. Kulsuma, holding tightly to her two sons, was still looking for her daughter.

We are all going to die, she thought to herself. The screaming continued.

The captain and crew of the Bravo abandoned ship, leaving more than 500 hungry and thirsty passengers adrift. © UNHCR / Younghee Lee

THE BRAVO

On the Bravo, rations had all but run out by 9 May, as the boat idled in the Malacca Strait, about 200 kilometres north-east of Lhokseumawe, Indonesia. The two massive cooking pots on deck were empty. For days, the passengers’ meals had been even sparser than the usual scoop of rice and dried chilli, so it was a surprise that Saturday when their food came early, and with extra rice and water.

Finally, after a hundred days at sea, they might finally be going to Malaysia.

Rehana* had not eaten so well since her wedding four months earlier, at her in-laws’ home in north Maungdaw. The groom, living in Penang, Malaysia, did not attend the ceremony but joined his bride on a video chat the next day. They had spoken on the phone before, but this was the closest they had come to meeting in person. Rehana was pleased that his parents were not asking for a dowry, and that her husband was willing to pay for her to join him in Malaysia.

“I was happy,” she recalls. “About the family and the man.”

A smugglers’ boat that was abandoned by its crew in May and drifted to Indonesia is docked in Lhokseumawe. Its passengers disembarked to temporary shelters. © Geutanyoe Foundation / Carlos Sardiña Galache

As she recalls the video chat, Rehana giggles like a teenager, because she is one. Rehana is 15. And the levity, even glee, with which she tells the story of her wedding cannot obscure the fact that she is an unaccompanied minor betrothed to someone she’s never physically met, a man who paid for her to be smuggled across a deadly sea.

“A child bride is a child at risk,” says a UNHCR child protection consultant who has researched early marriage among Rohingya refugees in Malaysia. There, UNHCR has identified over 120 Rohingya child brides, some as young as 11. Virtually every smuggling boat in these waters carries some young women and girls who are on their way to meet husbands they married over the phone, like Rehana.

“I was happy about the family and the man.”

Aboard the Bravo, hours after their first full meal in months, the 578 passengers’ hopes were crushed when the captain made a grim announcement. He had been instructed to abandon ship – “and let you drift in the sea.” In the dark, he showed them which way was west, and then left in a speedboat that had come to retrieve the crew.

Aisha*, a Rohingya teenager born in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, stands with the four children in a temporary shelter in Aceh, Indonesia, who floated with her from the Bravo to shore in a large cooking pot guided by fellow Rohingya passengers. © UNHCR / Tarmizy Harva

The Bravo sailed on. By dawn, it was close enough to land that passengers could make out trees along the Indonesian shore. Then, less than 100 meters out, the engine jammed. When none of the small vessels within shouting distance came to their aid, the men on the boat jumped into the shallow water and began swimming.

Those who could not swim—including many women and young children and a few men malnourished to the point of paralysis—were carefully lowered into the two empty cooking pots, now bobbing in the water. One man stretched a rope from the ship toward the shallow waters near shore, allowing Rehana and others to float slowly closer to land. When she finally stood on solid ground, it was for the first time in four months.

But it was not even close to where she had hoped to be.

“I’m thinking about whether I can have a peaceful future with my husband,” says Rehana, from a temporary shelter southwest of Lhokseumawe, on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. “Will it be a peaceful, happy life?”

Reportedly turned away by Malaysian and Thai authorities, the Charlie spent another week at sea before its passengers were rescued by Indonesian fishermen. © UNHCR / Younghee Lee

THE CHARLIE

Roshid* stood on the edge of the deck, ready to leap into the Andaman Sea. An empty jerry can was tied to his back to help him stay afloat. The crew of the Charlie had abandoned ship a few days earlier, so Roshid and a few other men decided to swim for help on behalf of their 400 fellow passengers. At least eight passengers had already died. All that was left on board to give the swimmers a shot of energy were raw chilli peppers. No rice, not a gulp of water. So they ground the chillis into a paste, swallowed and jumped into the sea.

“Most people were telling us not to,” says Roshid. But we’re half dead already, he thought. If not in the sea, he was going to die on the boat.

After swimming for over an hour, the coast seemed further away than ever, even as the Charlie had faded from view. So when the group spotted a fishing boat in another direction, they changed course. Half an hour later, the fishermen pulled them aboard and gave them food and water.

Spying the Charlie through their binoculars, the fishermen took Roshid and the other swimmers back and served a bounty of fish to the other passengers. A plane flew overhead, Roshid remembers, and later in the day two navy boats came and towed the Charlie through the night.

Malaysia’s Deputy Home Minister, Wan Junaidi Jafaar, announced the next day that, overnight, the Malaysian navy had provided food and water to, then turned away, a boat carrying around 300 passengers near Langkawi—that is, the Charlie—along with another boat near Penang, likely the Alpha. “What do you expect us to do?” he asked a reporter from the Associated Press. “We have been very nice to the people who broke into our border. We have treated them humanely, but they cannot be flooding our shores like this.”

Roshid holds up a family photograph, which he carried with him throughout his journey on smugglers’ boats from Myanmar to Indonesia. © UNHCR / Tarmizy Harva

By morning, the Charlie had been left to drift again. It was found on 14 May by journalists and the Thai navy near the Thai resort island of Koh Lipe, then provided rations by authorities before reportedly being towed back and forth across the Malacca Strait. Passengers told UNHCR that Malaysian authorities eventually escorted the Charlie into what they believe was Indonesian maritime territory. They then spent yet another night not knowing where they were, or how they were going to find their next meal.

One group of men on board had an idea. They rigged a sail using plastic tarp and used wooden planks as paddles. When they saw a large cargo ship, they waved their shirts to catch its attention. It worked. The cargo ship sent over three small boats with water and noodles, and fishing boats followed. But the fishermen said they needed to wait until evening to bring the Charlie to shore.

THE RESCUE

Early the next morning, on 20 May, the Charlie was rescued by a convoy of fishing boats near Julok, Indonesia. Across the Malacca Strait, in Putrajaya, the foreign ministers of Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand met to discuss what they called “the crisis of influx of irregular migrants”. At the end of the meeting, Malaysia and Indonesia agreed “to provide humanitarian assistance to [the estimated] 7,000 irregular migrants still at sea” and “offer them temporary shelter” so long as the international community resettled or repatriated them all within one year. The new arrivals joined over 99,000 refugees already in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Five days earlier, in the hours after fighting broke out on the Alpha, 820 of its passengers had eventually been rescued by fishermen near Langsa, Indonesia. Many survivors said they thought dozens of people died either from the fighting or drowning. Some personally knew an individual whom they saw drowning and never again. One man who swam for help and returned with a fishing boat to collect those still on board said he saw the bodies of seven men stashed in the engine room. Three-year-old Shahira Bibi died of tetanus five days after reaching Indonesia. The woman who jumped with her two-year-old son never found him. Another woman saw both her parents hacked to death. And multiple survivors all said they recognized the three bodies of Yasin’s parents and sister. That adds up to at least 14 people who would still be alive had they disembarked prior to the fighting.

In the week after the rescue, at a temporary shelter in Langsa, Kulsuma was still searching for her daughter, Setara. After saving her sons from being pulled below deck, Kulsuma had looked out at all the bodies in the water, and thought she saw Setara being rescued by a man. A fishing boat had come to their aid. When Kulsuma herself was later rescued directly from the Alpha, she was sure she saw Setara again, waving from another boat. “Setara,” Kulsuma shouted across the water. “Don’t worry.”

But in the shelter in Langsa where almost 700 survivors from the Alpha were taken, Setara was nowhere. “I was mad looking for her,” remembers Kulsuma. “Nobody knew anything.”

UNHCR staff found Setara days later in another shelter in Langsa, where a smaller group from the Alpha had been taken. After Indonesian authorities were notified, Setara was reunited with her mother and two brothers in early July.

At another temporary shelter in Medan, the provincial capital of North Sumatra, Abdul Jolil, the man who tossed wooden planks to the drowning family from the Alpha, tells UNHCR he used to be a driver in Kyauktaw, Myanmar. He has four daughters and two sons, and whenever he starts talking about them, he cries.

At 37, Abdul Jolil is older than 93 per cent of the male Rohingya passengers interviewed by UNHCR—two thirds are 21 or younger. Men like him step onto the smugglers’ boats not to reclaim their own future, as the younger passengers do, but to secure one for their children.

Abdul Jolil explains that he hasn’t been able to drive to non-Rohingya communities since violence erupted in 2012. After struggling and failing to provide for his children, he figured he could do more for them from Malaysia. “They have nothing,” he says, and cries again.

Abdul Jolil’s second son is 10, the same age as Yasin, the boy whose parents’ and sister’s bodies floated to the surface of the water after they drowned off the side of the Alpha. After the Alpha’s rescue, Yasin’s aunt, younger brother and another sister were registered by UNHCR in Langsa. They all believed Yasin had died, too.

Then, on 28 May, UNHCR registered a final group of Rohingya also rescued from the Alpha, who were being sheltered in Medan. The 12th person registered that day was a young boy who said he was 10 years old, and that his whole family—his parents, brother and two sisters—had drowned. It was Yasin. In the water, he had found a perch atop the wooden planks Abdul Jolil had thrown overboard. Yasin’s uncle and two other Rohingya men swam around the makeshift raft and guided it for hours, until a fishing boat found and rescued them.

UNHCR staff texted photos of Yasin and his siblings back and forth to confirm their identities. Yasin’s sister, whose eyes had been vacant for days since the deaths of her parents, was thrilled at the sight of Yasin. “She was soooo happy”, reads one of the texts. “She was chanting bhaiya bhaiya”. Brother, brother.

Rohingya men talk to UNHCR staff about their experiences at a temporary shelter in Lhokseumawe, Indonesia. © UNHCR / Tarmizy Harva

THE AFTERMATH

It is raining in Rakhine State. Floods have devastated the region, killing over 100 people and displacing tens of thousands of others. Yesterday it rained, today it rained and tomorrow it will rain again. It will rain every day, for hours, until September. Then the winds and the waters will settle, and the seven-day sea route to Thailand and Malaysia will open up again, wide as the Bay of Bengal.

Despite everything—the increased scrutiny by authorities, the widespread media coverage, the haunting images of starving people stranded in the ocean—little has changed. The number of Rohingya and Bangladeshis leaving their homelands by boat dropped dramatically in May, once the crisis unfolded, but that is what happens every May, when the rains begin. And every year, after a lull during these monsoon months, the traffic picks up again in September and October. Last October, an estimated 13,000 people embarked on smugglers’ boats in the Bay of Bengal, the most ever recorded in one month.

In late June, UNHCR met with Rohingya community leaders in Malaysia to get their sense of how, if at all, the boat movements had been affected by all the attention they had received. There was a general consensus that although the movements had been shut down temporarily, their re-emergence was inevitable, possibly as soon as this September. A couple of contacts had heard that smugglers were already recruiting new passengers in Maungdaw.

Yasin, from Myanmar, was orphaned in May when his parents drowned after jumping from a sinking smugglers’ boat off Aceh, Indonesia. © UNHCR / Keane Shum

But simply knowing about these movements is not enough; they have been known for years, and still hundreds more die every year. In 2014, an estimated 750 people attempting the journey died somewhere in the Bay of Bengal or Andaman Sea, and 370 more so far in 2015, including at least 70 on the boats cast adrift in May.

Something else remains unchanged. At the shelter in Medan, after months confined on a squalid ship and the carnage he witnessed at sea, Yasin nevertheless appears healthy and well balanced, active and open. His uncle and the two other men who ferried him on their two-plank raft keep a close watch on him, as does Abdul Jolil. But Yasin and his younger brother and sister remain orphans. The last image they have of their parents is of their corpses floating past the Alpha as it sank. That will never change.

In the courtyard of the shelter, Yasin’s uncle overhears a conversation about whether, come September, people will get on the boats again. As some of the men question why anyone would want to go through what they did, he steps into the debate.

“If there are still boats running,” he says. “People will come.”

*Names have been changed for protection reasons.

This article was produced by UNHCR’s Regional Maritime Movements Monitoring Unit in Bangkok, Thailand. Since June 2014, the unit has interviewed over 1,000 refugees and migrants who have travelled by sea in south-east Asia, including over 600 who were aboard the boats abandoned by smugglers in May 2015. This account is based on interviews with survivors and their relatives, as well as media reports. The primary contributors were Keane Shum, Muhammudul Hoque, Sarah Jabin, Fahmina Karim and Saw Myint.