“Juliette” shows other sex workers how to use a condom during a meeting at Lushebere camp. © UNHCR/Brian Sokol

The 17-year-old girl – I’ll call her Juliette – unrolls a condom in front of a dozen women at the community centre in Lushebere camp, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). What she teaches them here today may change their lives forever.

Her demonstration is part of an effort by aid groups to educate sex workers about HIV/AIDS. Juliette, of all people, knows how important it is; for four years, she has been one of them.

“I do this because I have no father, no mother. I lack everything, and this is why I started,” she tells me when I visit her at the camp in Masisi, in North Kivu province. “While doing this I had a child, and today I don’t have the means to live.”

Lushebere is one of several camps created in 2007 to shelter people fleeing conflict and violence in Masisi territory. It hosts nearly 5,000 internally displaced people, or IDPs, and despite recent relative peace in Masisi most are still too afraid to go back home. One reason is that insecurity still prevails in their villages of origin. Another reason is that many of them have lost everything: their homes, their land and all their possessions. Some have nowhere to go back to.

Young girls and women are particularly vulnerable. Many struggle to find the means to feed their families, especially now that funding shortages are forcing aid organizations to cut food rations and other assistance to the displaced.

“I have no father, no mother,” she tells me. “I lack everything, and this is why I started.”

To earn enough money to buy food for their children, some of the girls and women have been turning to sex work.

“I saw others doing it,” Juliette explains. “I had no food. I was going to school. A man came to see me. He told me that he would pay for the school [fees] for me. I did it. But he did not pay the school for me. He did not give me anything.”

One year ago, UNHCR and three of its partners – Belenfance, Search for Common Ground and International Emergency and Development Aid (IEDA) Relief – started a project here with the aim of preventing HIV/AIDS, sexual violence and exploitation of children, as well as improving reproductive health and preventing unplanned and unwanted pregnancies.

A 2012 study published in The Lancet found that HIV prevalence was nearly six times higher among women who sell sex than in the DRC’s general population, yet at the start of the project, 86 per cent of the sex workers in Masisi said that they knew nothing about HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases.

“I show them how to go to the health centre for family planning,” Juliette says. “I teach them how to work with a condom, how to protect themselves.”

“I was working without a condom,” Juliette tells me. “I was scared by HIV/AIDS. I was scared to give birth to too many children. Today, I say ‘thank you’. I learnt to work with a condom, how to plan birth. I saw that if women continue to do this, they risk falling sick and having many children. So I decided to become a peer educator. I show them how to go to the health centre for family planning. I teach them how to work with a condom, how to protect themselves. I organize meetings and I also go door to door to distribute condoms.”

In Masisi IDP camps, UNHCR and its partners work together with local residents, community leaders and the owners of the bars where sex workers go to find clients. The campaign also aims to prevent stigmatization of sex workers and sexual exploitation of children.

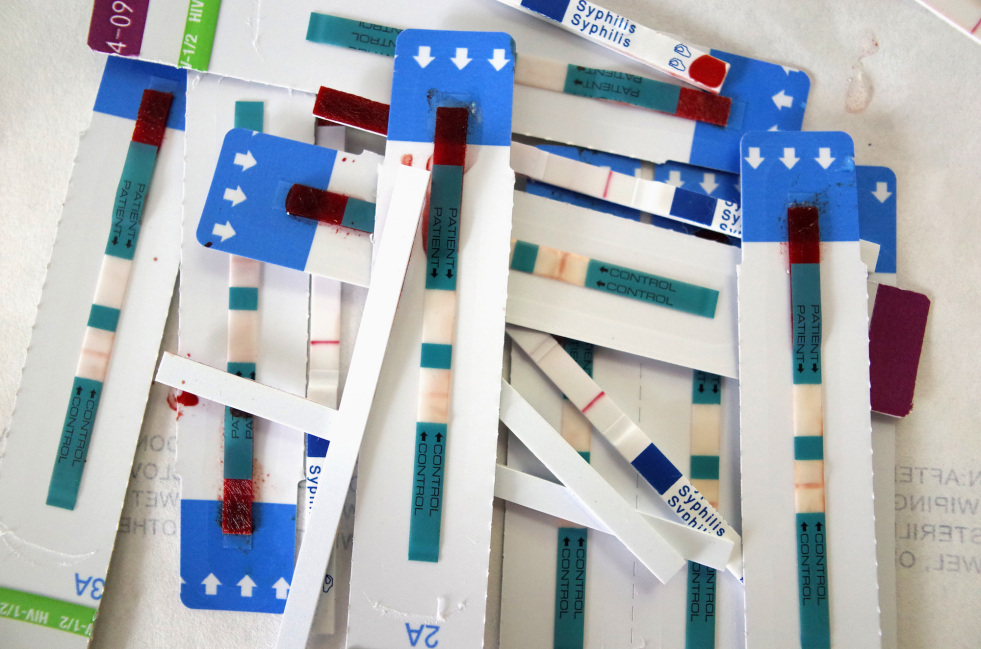

Used STD tests await disposal at the health center in Kitsule, North Kivu. HIV and syphilis tests are able to give results within three minutes. © UNHCR/Brian Sokol

“Talking to the clients is delicate, as well as to the owners of the bars,” says Mustapha Busomoke, who coordinates the project. “That’s where minors were exploited. We explain that minors have a special protection and are not ready for sexual relations. We do large campaigns and inform the entire population about the law and the bad practices. Now many people understand that sexual relations with children is prohibited by the law and is dangerous for children.”

As part of its work here, UNHCR is also helping sex workers and child victims of sexual exploitation to go back to school or generate their own income.

“I had left school but Belenfance told me that they would help me go back to school,” says Juliette. “I am in secondary school. I started yesterday. But when I am at school, I don’t know how to find money. When I leave school and if I find the man who can give me money to eat at night, I do it. I do it in my house. I do it with the one who comes. I tell my neighbours to look after my child. Not everyone pays me. Half pay, the others don’t pay.”

“If I had known about contraception before, I would not have given birth to all these children,” says Denise*, a 35-year-old mother of six.

Mariana Nyirarukondo, 33, receives a contraceptive implant from Dr. Kalibongo Raymond as part of the family planning services offered at the health centre in Kitsule, DRC. © UNHCR/Brian Sokol

To help women avoid unwanted pregnancies, UNHCR supports a family planning unit at the health centre of Kitsule in Masisi. The unit provides advice on family planning as well as access to contraception. It also provides anonymous testing for HIV and manages other sexually transmitted diseases.

“If I had known about contraception before, I would not have given birth to all these children,” says Denise*, a 35-year-old mother of six. She came to Lushebere camp alone in 2007. Both of her parents are dead, so she has no family apart from her children. “I am looking for men to earn money. I look for men in bars. Sometimes I find, sometimes I don’t. Maybe only three pay during a week. Sometimes it can be that 10 don’t pay during a week.”

Thirty-five-year-old Marie* shares a similar story. She has seven children. Her husband was killed in 2010 when he returned to their village to see if it was safe enough for the family to go back home. In 2012, unable to take care of her family, she started as a sex worker to earn money.

“Feeding the children was a big burden for me,” Marie tells me. “When I saw the others doing this activity, I also started to be able to take care of my children. In this activity, I had a child, but today I have a contraceptive implant. I can’t accept to be pregnant again. It is thanks to this project that I have known this.”

More than anything else, these women hope for long-term peace that will allow them to go back home, regain access to their land, build a new home and restart life in their villages.

Over 900,000 people are still displaced throughout North Kivu Province. One by one, they are learning how to protect themselves and their future.

* Name changed for protection reasons.

Written by Celine Schmitt