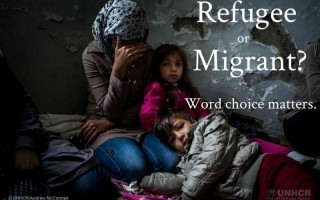

Natalia Artiukh and her daughter, who moved to the hospital from Zaporizhia, Ukraine, in June with other family members. © UNHCR/Nikolay Stoykov

When Nata Ellis, a tech entrepreneur originally from Odesa, first heard about the deserted hospital in her adopted city of Plovdiv in Bulgaria, she could already see its potential as a shelter for refugees forced to flee the war in Ukraine.

There was no water or electricity, and the interior was in complete disarray, with paint peeling off the buildings’ crumbling concrete walls. But it was free, donated by the municipality, and Ellis – who has called Plovdiv home since leaving Ukraine in 2016 – was determined to bring it back to life for the sake of the numerous women, children and older people in dire need of a place to stay.

“Within the first few days of the war we started a donation collection centre and with the help of family, friends and associates we quickly gathered food, medicine, blankets and bandages, but as things quickly escalated, we realized that more needed to be done,” said Ellis as she walked through the first few floors of the now refurbished hospital.

Together with help from refugee volunteers and donations from businesses, local authorities, NGOs and the Bulgarian public, Ellis has managed to renovate the first three floors of the four-storey building since taking on the project in March.

Under the auspices of her charity, the Ukraine Support and Renovation Foundation, the refurbished hospital finally opened its doors in June and is currently home to 130 refugees, including 51 children.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is currently repairing the entire fourth floor in addition to providing mattresses, blankets and kitchen sets to meet the centres’ growing needs, while the municipality is assisting with electricity, heating and food.

“Our protection teams who are on the ground helping refugees in Plovdiv identified this grassroots project for support, and this participatory approach including the local administration, municipality, refugees, host community and private sector creates the sense of belonging, which in turn creates inclusion and integration,” said UNHCR Representative in Bulgaria, Seda Kuzucu.

Families live together in communal bedrooms, and the reception centre is equipped with four kitchens per floor to allow refugees the freedom to prepare their own meals. In the storage area, refugee women help sort and catalog donations of clothes for wider distribution. Although the majority of the Ukrainian children attend Bulgarian school, the center also offers daily Bulgarian and English classes, while electronics, computer and art therapy classes are held several times a week.

Ahead of the holidays, children have transformed the centre into a winter wonderland with handmade ornaments and Christmas trees located throughout the reception and common areas. The hospital hosted a two-day Christmas Bazaar where hand-made jewellery, toys, knitted items and handmade backed goods were sold to help raise funds for children’s gifts.

“The centre is very much like a little village or community in the sense that everyone helps with everything, from cleaning to looking after each other’s children when they need to go to work – people are each other’s support network here, not only during the time that they are staying at the centre but even when they decide to leave and rent a flat on their own,” Ellis explained.

Natalia Artiukh headed to Plovdiv from the heavily bombed city of Zaporizhia with her children, sister and nephew and niece in June after hearing news about the renovated hospital and its community spirit. She now assists with the day-to-day operation of the centre, where aside from helping people find work the community also serves as a support network.

“We try to give little pleasures to our children here so that they can adapt, and it really helps that we feel like a big family. Everyone is always supporting each other and we feel like we can rely on each other,” said Artiukh.

Retired engineer Remen Nedjalkov is one of the many Bulgarian volunteers that have decided to help, initially by donating food and blankets to eventually his time by sharing his passion – electronics. He currently teaches a two-hour electronics course twice a week to refugee children at the centre in one of the rooms which he has equipped himself.

“If these children can learn something from me and then share that knowledge with others it will help them grow, and hopefully for a few hours it will take their minds off all the other troubles they may be facing,” said Nedjalkov, as he demonstrated how a small water pump works to his group of students.

“I already feel like I am part of one big family.”

Despite the troubles back home, young and old alike have found solace in the community spirit here, like 61-year-old pediatric surgeon Igor Prohorov.

Prohorov fled the heavily bombed city of Kharkiv only recently and is currently the reception centres’ live-in doctor.

“I have only been living at the reception centre for the past few weeks, but I already feel like I am part of one big family, and for example I am always given homemade food,” said Prohorov.

“People really appreciate that there is a doctor living here in case there is an emergency and I often tend to patients at all hours of the night,” he added. “I am grateful that I have been given this solace at a time when I have lost so much.”

Originally published by UNHCR on 23 December 2022.