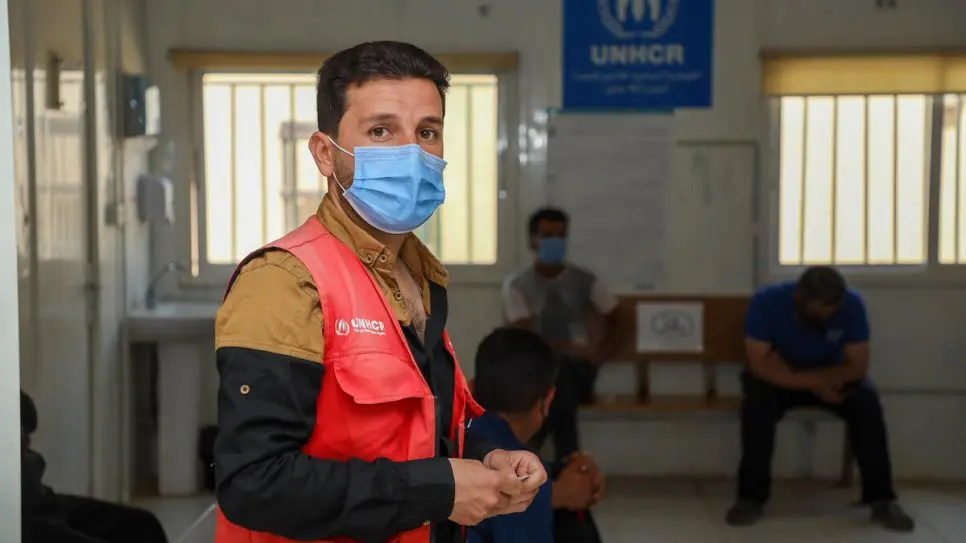

Syrian refugee health volunteer Sameeh is pictured outside a vaccination centre in Jordan’s Za’atari refugee camp. © UNHCR/Shawkat Alharfosh

As World Immunization Week aims to boost trust in vaccines, refugee volunteers work to combat misinformation and encourage older refugees to get vaccinated.

By UNHCR Staff

Sameeh has lived in Jordan’s bustling Za’atari refugee camp since 2013, when he fled his home in Daraa – just an hour’s drive north across the border – to escape Syria’s 10-year conflict.

The camp that today hosts 80,000 Syrian refugees is where he met and married his wife, and two years ago welcomed their first child. It was his connection to the camp and sense of community that first led Sameeh, 32, to become a health volunteer for Save the Children, one of UNHCR’s, the UN Refugee Agency’s, health partners in Za’atari.

DONATE TO HELP REFUGEES SURVIVE THE PANDEMIC

When he first started volunteering, he would visit families in his neighbourhood, telling them how to access health services and explaining the benefits of vaccinating their children against common diseases. But following the outbreak of COVID-19 last year, the significance of the role – and his commitment to it – increased.

“Before COVID-19, my role as a community health volunteer in Za’atari Camp was just like any other normal job,” Sameeh explained. “But now my job means something. You feel there is an urgency. Getting the COVID-19 vaccine could be a matter of life or death.”

“You feel there is an urgency.”

Jordan, which is currently home to more than 750,000 registered refugees including 665,000 from neighbouring Syria, was one of the first countries in the world to include refugees in its national COVID-19 vaccination programme and start innoculating them against the virus.

Priority for the jab is determined by the Ministry of Health, based on risk factors including age, chronic diseases and professions such as health workers. Since the start of the campaign in mid-January, almost 5,000 Syrian refugees living in the two main camps at Za’atari and Azraq have received the vaccine, with a further 13,000 residents registered on the government’s online platform and waiting for an appointment.

These figures are broadly in line with wider national trends, and the gradual increase in vaccination rates is a positive step towards fighting the virus. At the same time, further awareness campaigns are targeting refugees in urban areas to encourage uptake, with a focus on fighting misinformation on social media about potential side effects.

Sameeh says that much of his work has involved challenging false information circulating on social networks.

“People here are in general scared about the vaccine. There are a lot of rumors and worries about side effects. My job is to provide them with the correct information,” he said. “I would say that once I speak to people, the majority end up registering for the vaccine. Having a conversation is important.”

The efforts of Sameeh and his fellow volunteers reflect the goal of this year’s World Immunization Week, running from 24-30 April, which aims to promote trust in vaccines and maintain or increase their acceptance under the motto ‘Vaccines bring us closer’.

As more and more people get vaccinated, Sameeh takes pride in the fact that his work is having a positive effect. He also senses that some of the fear that gripped the camp during the earlier phase of the pandemic is starting to lift.

“We just want normal life back. As more people have received the vaccine things have got better. Especially now a lot of the elderly in the camp have been vaccinated,” he said. “We are very lucky that we can receive the vaccine here in Za’atari Camp. Refugees are treated like any other people.”

In Lebanon, similar initiatives were undertaken to encourage the 7,000 refugees in the country aged 75 years and above to sign up for the vaccine. They were among the first to be eligible for vaccination under the national roll-out plan drawn up by the country’s Ministry of Public Health, which covers all communities in Lebanon including refugees..

Teams of refugee volunteers have visited the homes of older refugees to talk to them about the benefits of inoculation and to help them register on the government’s website. UNHCR’s call center in the country has supplemented the outreach efforts, ensuring that all refugees aged 75 and over have been contacted about the vaccine.

Among them was Iraqi refugee Boulos, 75, who received a visit from one of UNHCR’s refugee volunteers who encouraged him to get the vaccine and helped him fill out the online form.

“I was hesitating, but then we had deaths [from the virus] near us, three of them,” Boulos said. “So I got encouraged and I thought ‘getting vaccinated is better’. Based on all that, I decided to get the shot.”

As well as protecting refugees from the virus itself, the vaccine has also offered a route out of isolation for many older refugees. Syrian refugee Amina, 85, had been living alone with her son Abdo since the start of the pandemic, unable to see her other nine children and many grandchildren.

Abdo was contacted on behalf of his mother, who is hearing impaired, by an outreach volunteer, who encouraged him to convince her to get the vaccine. After getting her shots, she is once again surrounded by her extended family.

“For Amina, the vaccine is not just about protecting her health,” said Dalal Harb, UNHCR Communication Officer for Lebanon. “The vaccine is an opportunity for her to reunite safely again with her family who care for her.”

Reporting by Lilly Carlisle in Za’atari refugee camp, Jordan, and Dalal Harb in Touline, Lebanon

Originally published by UNHCR on 29 April 2021.