Refugees and migrants from Cuba, Haiti and Venezuela take a canoe after crossing the jungles of the Darien Gap on their way to Panama. © UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

The dense jungle of the Darien Gap is increasingly becoming a site of transit for Venezuelans, Haitians and other people forced to flee.

By Sibylla Brodzinsky in Metetí, Panama

The sores on Mariana’s* legs from the rubber boots she wore on the gruelling trek through the jungles of the Darien Gap will soon heal. But the less visible wounds from the harrowing experience she endured in that patch of rainforest-covered mountains that separates South and Central America will likely take much longer.

Over five exhausting days, Mariana climbed impossibly steep, muddy hills, crossed rushing rivers, and was accosted by armed bandits. She is part of a growing flow of refugees and migrants from different countries throughout Latin America and beyond, willing to brave the inhospitable wilderness in their search for safety, protection, and a place to call home.

Mariana initially fled her home country of Venezuela to Colombia, where she tried to establish herself first in the border city of Cúcuta, and then in the capital, Bogota. But she struggled to support herself and her parents and six siblings back in Venezuela on the odd jobs that were all she could find.

“For us, it isn’t easy to find stable work and what there is just doesn’t pay enough,” she said, adding that many of her compatriots don’t seem to fare much better elsewhere in the region.

More than 6 million Venezuelans are living abroad amid widespread food and medicine scarcities and spiraling insecurity back home. Although some 2.6 million Venezuelans have benefited from residency permits or other visas in different Latin American countries, an almost equal number living abroad lack such papers.

Even for those with documentation, opportunities to restart their lives with dignity are scarce. This, coupled with the heavy economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, has forced many to embark on perilous journeys, joining the northward flow of refugees and migrants from Haiti, Cuba and elsewhere, who have also struggled to find stability in South American countries.

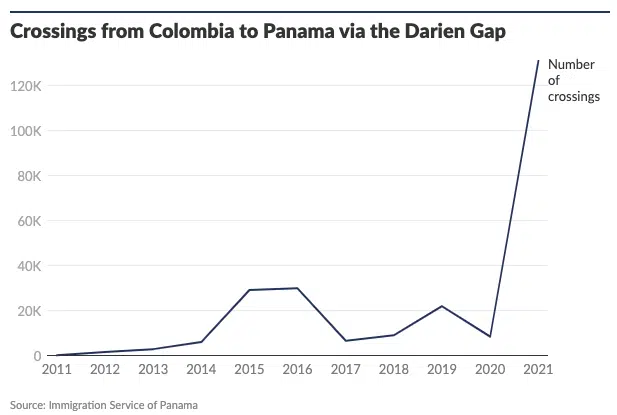

Despite the rough terrain and dangerous conditions, in 2021 alone, a record 133,000 people crossed from Colombia to Panama through the Darien Gap, according to Panamanian authorities, braving a gruelling trek few are prepared for.

“I had heard that it was dangerous, but I didn’t think it would be that dangerous,” said Mariana, now in the safety of the government-run Lajas Blancas Reception Centre in southern Panama.

On the third day of her journey, the group of Haitians, Senegalese, and Venezuelans she was travelling with encountered a band of three gunmen who stole the few possessions and little money they had.

One of them told the group to continue but pulled Mariana aside. He then raped her behind some trees.

“He told me, ‘If you behave and you don’t hide any money from me, you can catch up to your group. Otherwise, you’ll end up like the others.’” Mariana had seen the corpses of four women who had been shot on the trail, so it was frighteningly clear what he was referring to. More than 50 bodies were recovered from the jungle paths in 2021, according to news reports, although it is estimated to be only a fraction of all deaths on the trail.

At the reception centre, Mariana was given treatment to prevent an unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. She also filed a report with Panamanian prosecutors, who have deployed officials to the region to bring the perpetrators of such acts to justice.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is supporting refugees and migrants by providing temporary housing units, blankets, cots and hygiene kits at the government’s two reception centres. It is also providing support to remote indigenous communities to try to mitigate the impact of the hundreds of people passing through their villages.

Last year, the majority of those who crossed the Darien were of Haitian origin. Most had spent years in Chile or Brazil, after fleeing their homes in the wake of the deadly 2010 earthquake that flattened much of the island nation. But a mix of bureaucratic hurdles to renew residency permits, economic hardship and discrimination in their initial destinations drove many northwards, often with small children born in the countries where they first settled.

Dieufaite Sylvain, a Haitian national, crossed the Darien Gap with his wife Cherlie and three small children, aged 6, 5 and 2, all born in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Dieufaite had worked construction jobs there since leaving Haiti in 2013, but the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic made it harder and harder to find work. At the same time, the needs of their family still in Haiti, who relied on his financial support, grew amid the instability that flared following the assassination of President Juvenal Moise, and another earthquake in 2021.

The Darien Gap is a region of dense forest and mountains between Colombia and Panama. © UNHCR

It took the family 11 days to cross the jungle. They were accosted by bandits along the way who robbed them of all their money and their cellphones. After their food ran out mid-journey, they went hungry for five days. Twice, their youngest child, Esteline, was nearly swept away by the raging rivers they had to cross along the way.

“I was carrying her, and I fell, and she fell with me. God helped me,” said Dieufaite.

The family were now stuck at the Lajas Blancas Reception Centre until they could convince a bus driver to give them a break on the fare to the border with Costa Rica. They were thinking of settling there or going further north to Mexico. In 2021, Haitian nationals lodged the highest number of new asylum claims of any nationality in Mexico, at more than 51,000.

In the first two months of 2022, Venezuelans became the top nationality crossing the Darien at more than 2,400, nearly as many as crossed in all of 2021. In January and February, nearly 2,000 Venezuelans lodged asylum claims in Mexico, which represents almost a third of all claims by Venezuelans in 2021.

Antonio*, a Venezuelan who crossed the Darien with Mariana, said that although he spent six years in Colombia after fleeing Venezuela, the deteriorating security situation there drove him to move north. He said he has friends in Mexico and would try to settle there. After so much time on the move, “I just want to live in peace,” he said.

*Names have been changed for protection purposes

PLEASE DONATE TO SUPPORT MIGRANTS

Originally published by UNHCR on 29 March 2022.