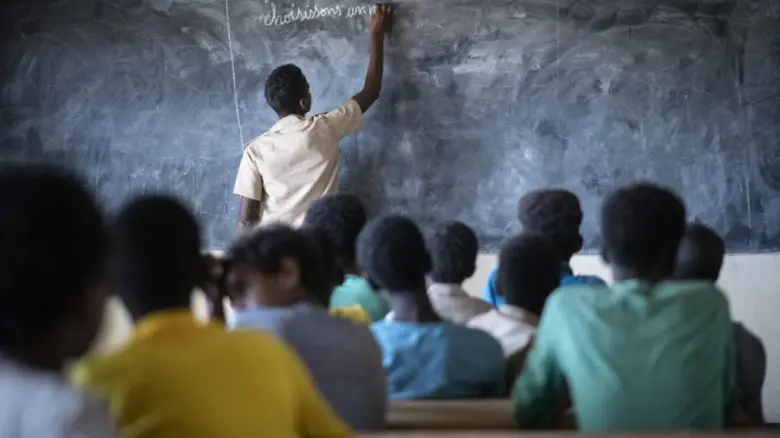

A Malian refugee student plays the role of teacher at a school in Goudoubo camp. Because of rising insecurity teachers no longer show up and students often teach each other. © UNHCR/Sylvain Cherkaoui

By end-2019, more than 3,300 schools were shut, affecting almost 650,000 children and more than 16,000 teachers.

At the end of the 2019 academic year, just as he was preparing to take his primary school leaving exams in northern Burkina Faso, a young Malian refugee called Oumar Ag Ousmane saw his hopes begin to fade.

With the violence that had been plaguing parts of the Sahel region for years beginning to rage in Burkina Faso, teachers at Oumar’s school simply stopped coming to work. Then they left the area altogether.

“I was very sad to have to stay home all day.”

That put Oumar’s education, and the education of thousands of other Malian refugee children who were then living in Mentao refugee camp, on hold.

“I was very sad to have to stay home all day and not be able to continue classes,” says Oumar, a reserved but determined teenager, now 17 years old.

It was a bitter blow. Growing up, there had been no school to go to in Oumar’s home town of Mopti, and after he and his family fled Mali in 2012 as violence was igniting there, life in Mentao camp had given him his first taste of an education.

To keep his schooling going, the boy’s father decided to take him and his siblings to Goudoubo refugee camp, further to the east. There he was registered in a school in the nearby town of Dori, hoping this would allow him to sit the crucial exams that let him progress to secondary level.

But more disruption lay in wait. “The following school year, as soon as the school year started, the same security issues continued in Goudoubo,” he says. “I was very disappointed that once again my school closed and that I was not able to finish the new school year.” Oumar is over the usual age to start secondary school, something which is common for refugee children, particularly where education is disrupted and there are no accelerated education programmes available.

In Burkina Faso alone, over the past 12 months the number of internally displaced people rose five-fold, reaching 921,000 at the end of June 2020. The country is also host to nearly 20,000 refugees, many of whom have recently fled the camps – seeking safety in other parts of the country or even returning to their homeland.

Across the Sahel, millions have fled indiscriminate attacks by armed groups against both civilians and state institutions – including schools. According to UNICEF, between April 2017 and December 2019 the number of school closures due to violence in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger rose six-fold. By the end of last year, more than 3,300 schools were shut, affecting almost 650,000 children and more than 16,000 teachers.

In Burkina Faso alone, 2,500 schools had closed because of the violence, depriving 350,000 children of access to education – and that was before coronavirus closed the rest.

Malian refugee children study at an UNHCR-supported primary school in one of the refugee camps in Burkina Faso. © UNHCR/Paul Absalon

On September 9th, the UN will mark the first International Day to Protect Education from Attack, with the General Assembly condemning attacks on education and the military use of schools in contravention of international law.

In a ground-breaking report, to be published on September 3, UNHCR warns the twin scourges of COVID-19 and attacks on schools, targeting teachers and pupils, threatens to destroy hard-won gains in refugee education and destroy the dreams of millions of youngsters.

Gunmen Break Into Kaduna School, Abduct Students Preparing For Exams | Sahara Reporters https://t.co/NfjMggX97N@GovKaduna @PoliceNG pic.twitter.com/VFaidFarZ6

— Sahara Reporters (@SaharaReporters) August 24, 2020

This year, Oumar thought it was third time lucky. His family moved a few miles down the road from Goudoubo camp to Dori, and he was able to start his first year of secondary school in spite of being older than most of the other students. “Everything was going smoothly,” he says.

“But classes had to stop again – this time because of the COVID-19 outbreak.”

Since 1 June, the three school grades that were due to take exams this year have reopened and UNHCR is doing what it can to find places for refugee children.

For the others, UNHCR, with the support of Education Cannot Wait, began buying radios for primary and secondary refugee students to ensure they had the same access as their Burkinabe peers to lessons being broadcast over the airwaves. UNHCR is also working with governments to enable emergency education for displaced children and youth via access to safe distance learning alternatives.

As he waits, Oumar refuses to be downhearted. “I still have the hope that the situation will improve so that I can go back and finish my education,” he says.

Originally published on UNHCR on 27 August 2020