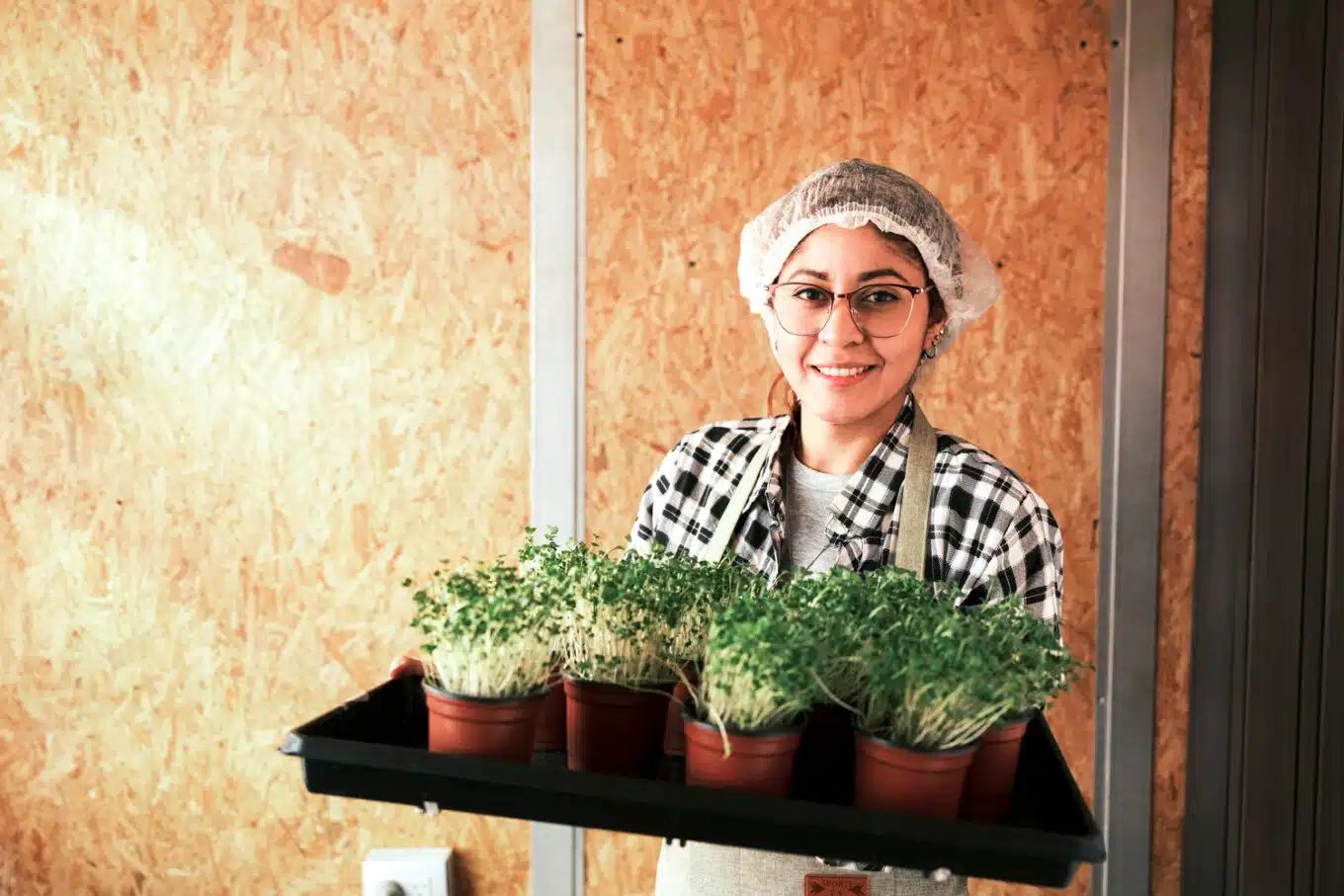

Abelis Carrillo, from Venezuela, working at Loopfarms, a start-up in Córdoba, Argentina. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Abelis Carrillo has found hope and a purpose working for an innovative start-up in Córdoba that uses cutting–edge technology to grow food in urban settings.

By Ilaria Rapido Ragozzino and Mercedes Pérez Bustillo

Mauro Barberis, co-founder of Argentinian start-up Loopfarms, likes to joke about how he met Abelis Carrillo: “We met through speed dating … but for companies and applicants!”

In just a few minutes, an instant connection sparked between the Argentinian chemical engineer and the Venezuelan agricultural engineer. It was an encounter that changed Abelis’s life.

She never imagined that her quest for job opportunities would lead her to cultivate microgreens in the heart of Córdoba, a city in central Argentina.

Hailing from a region known as “the breadbasket of Venezuela”, Abelis, 29, grew up surrounded by vast fields of sunflowers, corn, and sugarcane. Her love of nature led her to study agricultural engineering. She hoped to live and work in the countryside, caring for the land and animals. But she had to give up her dream when, in 2017, Venezuela’s deteriorating economic and social situation and lack of access to essential basic services forced her to leave the country. After travelling alone to Argentina, she met up with her partner who had fled there months earlier.

A model for sustainable food production

She faced challenges trying to establish herself in a new country, but everything changed when she met Mauro. At Loopfarms, an innovative company that promotes sustainable food cultivation, she found not just a job, but a passion. After working for five months as an intern, she now oversees the production of microgreens and edible mushrooms at one of Loopfarms’ facilities.

The start-up’s mission is to revolutionize urban agriculture and promote a sustainable food production model. The company uses cutting-edge technology, such as biogas and hydroponics, to cultivate microgreens indoors, making the most of available space in urban settings.

“They don’t need a lot of water and soil, and their production cycle is shorter,” explains Abelis.

Loopfarms collects organic waste generated by nearby restaurants to produce biofertilizer, which is then used to feed the sprouts. “It’s about taking advantage of resources that would have been lost, through the recycling of organic waste,” says Mauro.

Globally, agriculture and food production generate nearly a third of human-made greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. By contract, Abelis’s work at Loopfarms is mitigating climate change by using minimal transportation, land and water to produce food that is packaged in returnable containers to avoid plastic waste.

Despite the challenges they face, refugees and displaced people like Abelis are playing a role in helping their communities adapt to the threats posed by the climate crisis. Given the right support, they have adopted sustainable practices and launched initiatives to protect local ecosystems and build resilience. Their involvement is crucial amid a crisis that is affecting the entire world but is particularly impacting vulnerable people living in regions beset by conflict and disasters.

Matching refugees with employers

Mauro and Abelis met at a “Cities of Solidarity” event in 2022, an initiative by UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, that unites different municipalities in the Americas to work together for the protection and inclusion of refugees and migrants. The activity – organized by the Municipality of Córdoba and the Foundation for Business Incubation (FIDE) with UNHCR’s support – allowed various companies to meet refugees with professional profiles relevant to their businesses.

In recent years, the number of refugees and migrants arriving in Argentina has increased. By June 2023, according to figures provided by government counterparts and compiled by UNHCR, this figure had reached over 230,000.

By providing employment and opportunities to displaced people like Abelis, Loopfarms is contributing to inclusion and diversity in the workplace.

“It seemed very commendable to give an opportunity to people who had to flee, to reinsert them in the labour market, especially if it can be linked to what they studied, what they were doing in their country of origin,” says Mauro.

Abelis takes part in a traditional Venezuelan dance class at the Casa de Migrante in Cordoba, Argentina. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

He and Abelis have become good friends. As they carry out their work, they enjoy discussing their roots and sharing their gastronomic traditions.

When the workday is over, Abelis sheds her apron and hairnet and puts on her sports clothes to attend Venezuelan dance classes. Dancing alongside around 30 other Venezuelans, she reconnects with her roots and feels closer to home, particularly to her parents, whom she misses dearly.

“I’ve been dancing since I was little. When I dance here, it transports me back to Venezuela. I feel very emotional, sometimes I even cry,” she says.

Although she misses her homeland, Abelis has found hope away from home by working at Loopfarms: “I hope to stay here, keep learning, and growing,” she says. “Argentina is my home now. I hope to soon have nationality and be able to say, ‘I am Argentinian’.”

Originally published by UNHCR 8 April 2024